Ferris Bueller and the charm of the sovereign

He lies, he runs, he wins. But Ferris Bueller’s rebellion is no rebellion at all—it’s the system winking back.

"Bueller?... Bueller?"

It’s one of the most iconic scenes in American film: a monotone economics teacher stares out at a comatose classroom, rattling off the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act while the camera pans across glazed teenage faces. In the seat where Ferris Bueller is supposed to be, there’s only absence—a name called out to no reply. It’s meant to be a joke about high school boredom. But it also performs something deeper. Ferris is missing because he doesn’t need to be there.

While his classmates are stuck learning about economic collapse and protectionist policy, Ferris is off dancing in a parade, slipping past maître d’s, and monologuing to the camera with zero consequence. He doesn’t just skip school, he floats above it, buoyed by a system that not only tolerates his behaviour but quietly insists on it. The Great Depression may have been caused by bad policy, but Ferris Bueller is the kind of American the post-Depression system was built to reward: charming, white, frictionless, always winning.

The great lie of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is that it’s a story about rebellion. It’s not. It’s a story about sovereignty—the ability to operate outside the rules while still being protected by them. Ferris doesn’t face consequences, because he was never meant to. He performs resistance, but only to reaffirm his place at the centre of a world that exists to let him bend it. And the deeper twist? We’re in on it. The movie wants us to love him, and in doing so, we become the final pillar of his myth.

The illusion of risk

Ferris Bueller runs, but he is never running from real danger. The movie goes out of its way to suggest tension—there’s a ticking clock, a vindictive principal, a suspicious sister, and parents who might return home at any moment. Ferris hops fences. He dodges neighbours. He sprints across lawns to beat the garage door. On paper, it’s a chase. But in truth, it’s choreographed pageantry. Every risk is aesthetic. Every escape is a foregone conclusion.

This is not suspense so much as it is ritual.

Ferris isn’t fighting the system. He’s demonstrating its flexibility, showing how much it can be bent by someone who knows how to smile at the right time. He breaks the rules, yes. But only because the system was built to absorb that breakage, and in doing so, make itself seem magnanimous.

In Homo Sacer, Giorgio Agamben writes about the figure of the sovereign, someone who stands outside the law but still defines its limits. The sovereign is the exception that proves the rule, the one who can transgress without punishment because the system secretly depends on them. They don’t just escape justice—they authorize the escape itself.

Ferris is our sovereign. He skips school, fakes illness, steals a car, hijacks a parade, and narrates the movie like he’s producing it in real time. But he is never caught. Never punished. The adults who threaten his freedom are reduced to slapstick (poor Rooney), and the one person who sees through him—his sister—eventually joins his cause. Even Cameron, the closest the film comes to consequence, exists to absorb what Ferris never has to feel. He pays the emotional bill for the day off, while Ferris floats untouched.

The movie manufactures the appearance of risk while ensuring Ferris is never truly in danger. And this is the real trick: it isn’t about consequence, but about celebrating the kind of person who never has to worry about it.

Effortless American success

Ferris Bueller doesn’t change. He doesn’t grow. He doesn’t struggle or reckon or resolve. And that’s the point.

Where most protagonists face tension that transforms them, Ferris floats untouched through the day’s events. His charm is his shield, his smile the mechanism of propulsion. He simply moves from scene to scene collecting experiences as if life were a catalogue to browse. And yet, at the end of it all, he's rewarded not just with survival, but with admiration.

This is the dream that Ferris Bueller sells: not rebellion, but charm-fuelled reward. A version of American success where merit is measured not in effort but in likability, not in labour but in leisure. He doesn’t climb; he coasts. And still, everything works out.

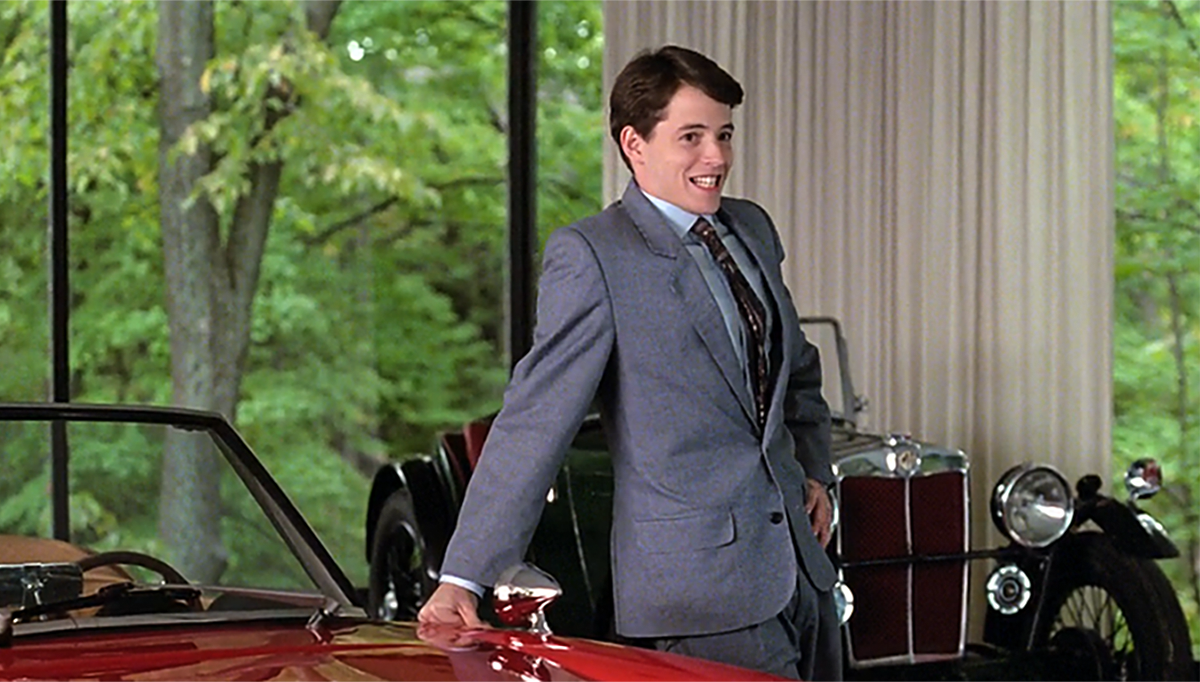

That’s what makes the film so seductive. Ferris isn’t mega rich, but he moves like someone who has inherited something more powerful than wealth—cultural immunity. He navigates elite spaces without being challenged, inserts himself into public spectacle without resistance, and drifts through institutions that are rigged to protect him. His day off becomes a high-speed tour of cultural capital: art, luxury, performance, spectacle. But there’s no real gatekeeping because the doors are already open.

The subtle brilliance of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is how convincingly it sells this movement as freedom. It’s not. It’s permission—granted invisibly by a system that hides its constraints behind the illusion of ease. Ferris doesn’t make the rules feel irrelevant; he makes them feel like they’ll bend for the right kind of person. That sentiment defines his advice to Cameron, but more strategically, his running metafictive commentary invites the viewer to believe that privileged person might be us.

It’s the same sleight of hand that animates our love of celebrity wisdom. Lines like "If you put your mind to it, you can do anything" ring out across commencement stages and social media feeds, not because they’re true, but because they preserve the myth that effort alone explains success. That’s capitalism’s favourite trick: to present exceptional outcomes as universally attainable, so long as you play the game.

Ferris doesn't showcase effort per se (quite the opposite), but he still plays the ideological decoy, proof that the system works—so long as you’re charming, confident, and savvy. And in contrast, Cameron breaks. He's the one who feels the weight of the day, who confronts his family, who stares into the abyss of the shattered Ferrari and says something has to change. His catharsis is real.

There’s a moment in the Art Institute that passes almost wordlessly, but it’s the emotional core of the film. While Ferris and Sloane flit through the galleries like tourists at play, Cameron stops. He stares into Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, a painting famous for its stillness, precision, and calm sense of order.

At first glance, it’s idyllic. Leisure made eternal. A perfect afternoon, just like the one the group is putatively having. But the longer Cameron looks, the less he sees a scene, and the more he sees fracture. The brushstrokes, the points of colour, the atomization of what once felt whole. The closer you get, the less real it becomes.

The film never speaks it aloud, letting it sit in an emotional register outside of exposition, but Cameron sees what Ferris never has to. The American dream isn’t seamless. It’s a million fragments straining to hold an illusion together. Up close and under examination, the system isn’t generous. It’s scattered, incoherent, uncaring.

Ferris skates on the surface because looking closely doesn't pay. To remain sovereign, he can’t afford to acknowledge the system as system. He must move through it as if its privileges are natural, inevitable, deserved. Cameron, by contrast, doesn’t have an epiphany so much as an encounter with the real. He sees the world not as a cohesive scene, but as lines and dots awkwardly assembled into a frame that only holds its shape from a distance.

And in that silent stare, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off finally admits its own secret: the day off is a fantasy, a pretty picture filled with fractures for anyone who dares to look closely enough.

The audience as enabler

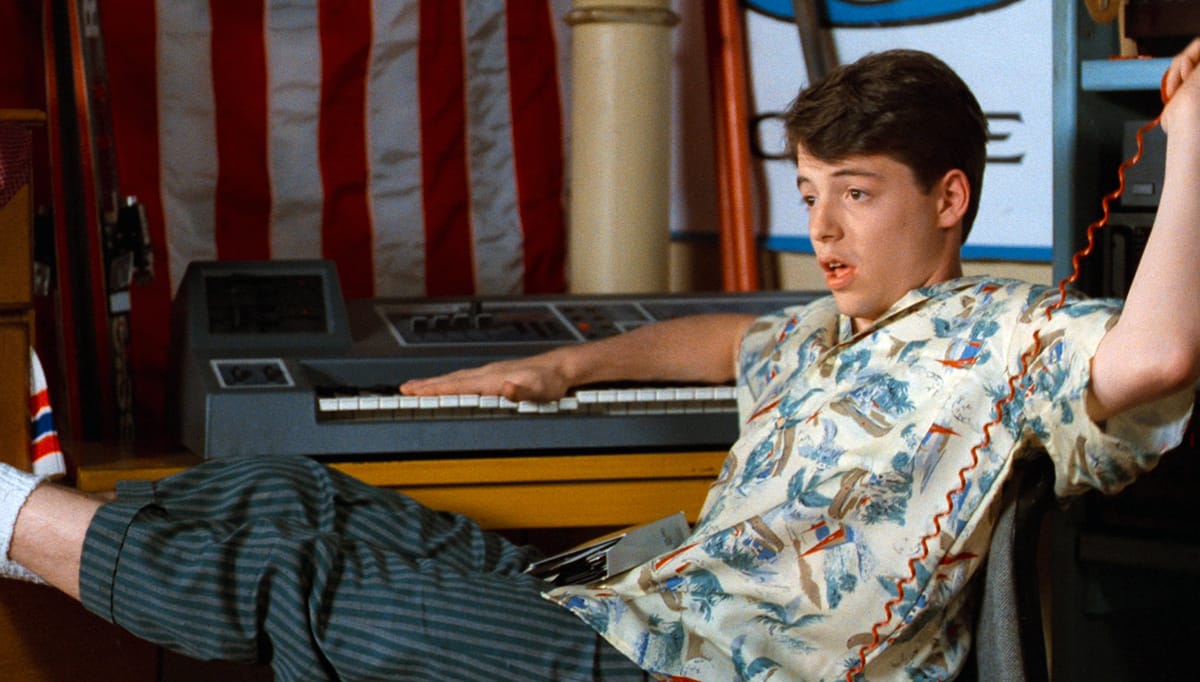

From the first moments of the film, Ferris speaks directly to us, charming the viewer as easily as he charms his parents. He tells us his tricks. He lets us in on the plan. He’s not just the main character, he’s the host, the narrator, the director of affect. He controls the frame, the rhythm, the mood. He defines the day, and we’re flattered to be along for the ride.

But this isn’t transparency. It’s actually a power move.

By bringing us in, Ferris defuses critique. He makes us complicit in his myth. We’re not watching him cheat the system in disgust. Far from it, we’re enjoying it, rooting for it, celebrating it. And when things seem like they might unravel, we know instinctively that they won’t. Because we’ve been trained to see Ferris as a natural winner, a benevolent manipulator, someone for whom the world bends.

That’s what makes his most quoted line so potent: "Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it." It sounds like wisdom. And maybe it is. But there’s a certain luxury that underwrites it. Only someone so untouched by consequence—so frictionless in his movements through the world—can hold this as his mantra. Ferris isn’t reflecting; he’s narrating. He’s curating an experience and branding it as revelation.

Compare this to Cameron. His best friend, we're told early on, "isn’t having any fun." He is consumed by inner reflection, but of a wholly different kind. Cameron’s day is not shaped by leisure but by dread—of his father, of his future, of himself. Where Ferris coasts through the world with unshakable certainty that things will work out, Cameron is immobilized by the opposite: the quiet suspicion that they won’t.

Even Jeanie, Ferris’s sister, seethes at his immunity. She follows the rules and still finds herself punished. Ferris breaks them and somehow floats. Her frustration isn’t just sibling rivalry; it’s the fury of someone who understands that the rules are real, and that they only bend for people like Ferris. She isn’t angry that the system is broken. She’s angry that it works exactly as intended: rigid for some, endlessly elastic for others.

As sovereign, Ferris’s so-called reflection isn’t really about presence at all. It’s about pleasure. The “stop and look around” he advocates is a tour through curated cultural capital: ball games, fine dining, luxury cars, art museums. It’s not about engaging with the world on its terms—it’s about mastering it, sampling it, styling it into a highlight reel.

Crucially, the line isn’t just offered to Cameron or spoken into the void. It’s delivered to us. It flatters the viewer with the illusion of shared insight, as if we too have earned the right to pause. But of course, we haven’t. We’re just watching someone who already has.

And then, having wrapped his perfect day and dropped his counterfeit wisdom, he dismisses us. "You’re still here? It’s over. Go home. Go." It’s not just a cheeky closing line—it’s an assertion of control. The sovereign doesn’t just escape consequence; he commands the narrative, ends the performance, and sends the audience away on his terms. We’re told the story is done, and we obey.

The smile that rules us

There’s a moment in the film—subtle but unforgettable—when Ferris stands at the top of the Sears Tower, forehead pressed to the glass, gazing out over Chicago. The city hums below. He’s not watching it so much as overseeing it. It’s tranquil, orderly, his. This isn’t the view of a teenager on the run. It’s the panopticon turned playground. A sovereign surveying the domain he’s already mastered.

Sloane stands beside him, poised, glamorous, and narratively passive. She smiles. She, too, floats. She plays queen for a day. But like so many figures in Ferris’s orbit, she has no arc of her own. She's there to reflect his charm, not complicate it. Even her quiet envy of Ferris’s certainty, her soft "you knew exactly what you were doing," is folded neatly into the performance of his perfection.

This is how the movie works. Not by hiding its mythmaking, but by styling it so well you want to believe in it. Ferris Bueller is the American fantasy in Ray-Bans: effortless mastery, no lessons, no loss. His day off isn’t a rebellion against the system—it’s the system congratulating itself. A ritual that reaffirms that charm beats labour, that consequence is negotiable, and that the right kind of person will always be forgiven.

It’s the first half of a Scorsese film.

The parade instead of the back entrance to the Copacabana. The Cubs game instead of the cocaine. The quiet Chicago suburb instead of the hollow glamour of Las Vegas or Wall Street.

Ferris lives in the part of Goodfellas and The Wolf of Wall Street before the paranoia, the indictments, the blood on the carpet. He floats through elite spaces with the ease of a steadicam—gliding, smiling, never tripping over the cords. But the difference is, in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the shot never cuts. The illusion never breaks.

This is the dream Ferris offers. It's not rebellion, but suspended youth. No consequences, no aging, no change. And the audience, like Sloane and Cameron, is asked to indulge the fantasy just long enough to believe in it.

And we do. We smile, we laugh, we wish we were him. Because Ferris isn’t just the sovereign of his world. He’s the sovereign we asked for and continue to mythologize.

No crash, no fall, no comeuppance. Just one perfect day, forever rerun, and a system that smiles every time we press play.

Interstellar and the impossible return

How can you get back home when you never really left?

Interstellar was sold as a hymn to love, endurance, and human ingenuity. Its trailers showed a world on the brink and the lure of salvation on the other side of the universe. And its marketing materials promised a future where human connection, not conquest, would overcome the abyss of extinction. Even within the film, the refrain seems clear enough: love transcends time and space.

But Interstellar is not a simple hymn. Beneath its soaring score and polished cinematography, it stages a deeper, more difficult tragedy—not the collapse of science, nor the failure of love, but the inescapable betrayal of nostalgia. It's not the inability to hold onto the past that haunts the film, but the realization that clinging to the past is the only frame through which human meaning can persist, and that this clinging inevitably fractures what it seeks to preserve.

From its opening frames, Interstellar reveals a world already spiritually dead: crops fail under suffocating dust; history is rewritten to erase exploration; survival demands the slow, compulsory forgetting of dreams once thought essential to human identity. The Earth-bound survivors are struggling for more than breath; they're struggling to unlearn their myths.

In this context, Cooper’s departure isn't simply a heroic gamble or a selfish escape. It's an act of wounded faith: the desperate belief that by betraying the immediate bonds of love and memory, by becoming the ghost of his daughter’s past, he might somehow preserve the mythic thread that gives human life meaning at all. His journey outward is also a fall inward, into haunting, into estrangement, into the permanent ache of nostalgia.

And the still deeper tragedy Interstellar stages is that there is no outside to this condition. Not even through time dilation, not even with the help of higher-dimensional beings, can humanity escape the gravity of its own longing. Every attempt to transcend memory collapses back into it.

Let's trace that collapse, from Cooper’s necessary betrayal, to Murph’s inherited burden, to the haunting architecture of memory itself. It's a journey into the mythic structure that defines Interstellar: not a pure Kierkegaardian leap into absurdity, but a desperate act of faith—one that risks everything on an almost, as Cooper answers the call of a future he cannot see.

His journey, and that of film itself, is not toward certainty or conquest, but toward the fractured rediscovery of origins that can never be fully reclaimed.

Longing for a life never lived

Cooper’s longing for the stars does not emerge from memory. It emerges from myth. The world he mourns—the world of ambition, exploration, of human conquest over the frontier—is already gone before Interstellar begins, if it ever truly existed at all.

But nostalgia in Interstellar is not merely the ache for a personal past. It's the reshaping of memory into myth—the transformation of longing into a story structure capable of surviving its own fracture. What Cooper mourns is not just lost history, but a mythic dream of human striving that never fully existed, except as a necessary fiction.

In the early scenes, we see Cooper drifting through the hollowed-out rituals of survival: fixing drones that have lost their purpose, tending to cornfields that will soon fail, raising children in a society that quietly punishes curiosity. When Murph’s teacher scolds her for bringing an old textbook to class, one that still teaches the Apollo landings as fact, we glimpse the quiet machinery of forgetting.

History is rewritten not out of malice, but necessity. Humanity can no longer afford to believe in limitless progress, or to live inside the fragile grace of wonder.

It's within this context that Cooper’s nostalgia becomes both dangerous and sacred. When he confronts Murph’s teacher, Cooper defends not just historical accuracy, but a vanished ethic of striving. Later he'll say, “We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.” The line is delivered almost casually, but it reveals the full architecture of Cooper’s character and of the film’s mythic tragedy.

Cooper is not merely chasing lost glories. He's enacting a profound refusal to accept a future stripped of mythic longing. His decision to join the Lazarus missions—to leave Earth, to abandon Murph—is framed not as escapism, but as a wounded commitment to meaning. He carries forward a fragile faith that something worth preserving still flickers in the ruins of human aspiration, a faith made both more urgent and more agonizing by the very presence of Murph, who embodies the wonder he fears the world is losing.

In choosing to leave, Cooper does not deny what is good in humanity; he sacrifices it, gambling that the thread of meaning she represents might survive even the betrayal his departure demands. This is the wound around which the entire story orbits.

Yet even Cooper’s nostalgia carries the trace of something stranger, a fracture seeded before the story even properly begins. We learn that Cooper’s career as a pilot ended not through choice, but through a crash linked to the very gravitational anomalies that will later open the path to the stars. In retrospect, the crash feels less like random misfortune and more like structural necessity: an unseen hand ensuring that Cooper would carry the wound of loss deeply enough to make the impossible leap when the time came.

His longing is not incidental. It's engineered—not by cosmic manipulators in any literal sense, but by the deep architecture of the story’s mythic necessity. Cooper must be broken, must be haunted, must carry the seed of nostalgia in its purest, most painful form. Without the crash, without the ache, his drive to preserve something pure would be compromised.

The name of the ship he joins is not incidental either. It's not called Hope or Discovery. It's called Endurance, a quiet acknowledgment that survival will not be measured by conquest or optimism, but by the ability to bear the weight of longing without succumbing to despair. Cooper doesn't seek a new beginning. He seeks a way to carry the wound forward, even knowing it can never fully heal.

In leaving Earth, Cooper doesn't betray the past. He preserves it — at terrible cost. His haunting of Murph, his own descent into myth and memory, is not an accidental tragedy. It's the only possible outcome once endurance, not salvation, becomes the true measure of survival.

The ghost behind the bookshelf (or gravity as nostalgia)

The first ghost in Interstellar is not a mystery to be solved. It is a wound made visible.

Murph’s room becomes the staging ground for a haunting long before the narrative delivers Cooper to the tesseract. Books fall from shelves. Patterns emerge in the dust. Murph believes, instinctively, that something, or someone, is trying to reach her. Cooper dismisses it, half-joking about "poltergeists," but the film lingers on the disturbance: the private space of memory disturbed, encoded with invisible grief.

The ghost is not supernatural. It's mythic. It's longing made physical—nostalgia collapsing into cause.

When Cooper later realizes that the gravitational anomaly in Murph’s room holds coordinates—the map to NASA’s hidden outpost—the haunting reveals its deeper nature. The very force that pulled Cooper from his crashed pilot’s seat, that severed him from the heroic frontier he never fully inhabited, now calls him outward again. Gravity itself, it would seem, bends to longing. What Interstellar stages is not just the persistence of memory, but the terrifying endurance of nostalgia.

Before Cooper departs, he seeks to make amends with Murph, recounting something his late wife once told him: “After you kids came along, your mom said something to me I never quite understood. She said, ‘Now we’re just here to be memories for our kids.’ I think now I understand what she meant. Once you’re a parent, you’re the ghost of your children's future.”

At the time, Cooper speaks these words gently, almost sentimentally. But within the film’s larger architecture, they sound a deeper, more haunting note. To love is already to become a memory. To be a parent is to become a ghost. Nostalgia is not a weakness or a distraction. It's the human condition—the only frame we have.

As he utters these words, Cooper is already his daughter's ghost. He's the architect of his own haunting, trapped in a closed causal loop where love, memory, and betrayal fold in on each other until gravity itself becomes an act of myth-making.

Murph’s childhood is defined by this haunting. She's not only abandoned by Cooper's physical departure; she's tethered to the residue of his impossible longing and to the fragile evidence that meaning still persists. Every falling book, every pulse in the dust, reasserts the inescapable truth: she lives inside the ruins of a myth that cannot die.

And yet, it's this very haunting that will shape her genius, her defiance, her refusal to let Earth's fading breath become humanity’s final word. Murph inherits not just her father’s pain, but the unbearable task of completing the myth he could only fracture. In Interstellar, the ghost behind the bookshelf is not an aberration. It is the architecture. It is the necessary fracture by which meaning, and endurance, will continue.

Murph’s inheritance of the myth is not without cost. Her brilliance is forged inside a fracture—the very fracture her father’s love could not avoid creating. She carries the dream of survival through the wound of abandonment. As TARS will explain to Cooper later, "In order to go somewhere, you gotta leave something behind."

Interstellar never allows nostalgia to exist without consequence. Every act of remembrance, every attempt to preserve meaning, deepens the scar that separates love from survival. The gravity of longing that haunts Murph’s childhood eventually curves toward a darker, harsher reality: that endurance is not always a matter of faith or love. Sometimes, it is a matter of betrayal.

It is this darker turn that Cooper himself must confront as he meets Dr. Mann, the figure who embodies what survival without myth, without memory, without meaning truly looks like.

Survival as betrayal of nostalgia

Mann doesn't cause Cooper’s collapse. He reveals it.

When Murph’s transmission reaches Cooper—the revelation that Plan A was a lie, that Earth's salvation was never possible—the myth he carried fractures. Cooper’s mission, once propelled by absurd faith in human endurance, shrinks into something smaller: a longing for return, for reunion, for the last embers of a life already lost.

It's after this collapse that Mann emerges, not as a simple villain, but as Cooper’s foil.

Mann knew Plan A was impossible. He left anyway. He participated in the lie because survival, even survival severed from meaning, had become his only compass. Mann embodies the future stripped of memory, stripped of myth, stripped of the human dream Cooper still carries as a wound—a dream most vividly alive in Murph herself.

"Don't judge me, Cooper," Mann pleads. "You have no idea what I’ve been through." But Cooper does know—because in that moment, he recognizes the terrible cost of abandoning nostalgia altogether. Without memory, without longing, survival becomes pure instinct: brutal, deceitful, monstrous.

Their confrontation is excruciating, not merely for its violence, but given the stakes it has on meaning. Cooper fights not to survive, but to preserve the last human claim that survival without love, without memory, is no survival at all.

Mann's death—sudden, chaotic, the airlock tearing open into vacuum—is more than punishment; it's mythic judgment. His is a paradigm that the film refuses to take root. The universe of Interstellar does not reward survival at any cost. It demands that survival remain haunted by the ghosts of meaning, even unto death.

Cooper survives not because he is stronger, but because he has already accepted that endurance is not the goal. It's human mythology and the meaning we derive from it that matters.

Mann’s failure is not purely moral. Abiding by Interstellar's terms of reference, it's structural. He represents a future in which humanity abandons the burden of memory, sheds the myths that once anchored it, and survives purely by its own imperative, consequences be damned. His betrayal is terrifying not because it's unthinkable, but because it's plausible.

Mann shows us what survival without nostalgia would look like: a future stripped of love, stripped of meaning, stripped of the ghosts that make survival human. Interstellar recoils from this vision. It insists—against odds, against evolution itself—that memory and longing must endure, and that myth is inescapable.

Cooper’s fall into the black hole is an act of faith that the fracture itself—the longing for what has always defined humanity—is worth carrying forward, even when survival tempts us to abandon it.

The end haunts the beginning

In the end, Cooper doesn't conquer space or find salvation. He falls deeper into myth, deeper into memory, and deeper into the gravitational wound that nostalgia has carved through existence. His plunge into Gargantua is not a new act of faith nor even an act of pure desperation, but the inevitable consequence of the leap he made before he left—the wounded promise to endure meaning even when the future offered no guarantees.

The black hole is not merely a cosmic obstacle but a mythic structure—a place where time collapses, where beginnings and endings fold back onto each other, where meaning survives only through fracture. Inside the tesseract, Cooper doesn't rebuild the lost world so much as he haunts it. He becomes the ghost Murph believed in. He sends the final pieces she needs to solve the equation, not to undo Earth’s ruin, but to preserve the memory of what humanity once tried to be.

Love becomes the mechanism by which memory travels. Gravity becomes the handwriting of nostalgia itself.

Cooper’s journey ends not with triumph, but with return, one that offers a muted homecoming. Murph, now old and dying, recognizes him more as the ghost she believed in than the father she lost. Their reunion is brief, formal, and surprisingly hollow given the ache that has tethered them across the universe. Her family surrounds her bedside, but they hardly acknowledge Cooper. He's not part of their lives, nor hers in a strict sense.

Murph, with mercy and final clarity, sends him away. She understands what he has become: a relic of a lost world, a fragment of memory that no longer belongs to the living. Cooper must return to Brand, his fellow nostalgic pioneer, to serve as an emissary for the memory he has sacrificed everything to preserve. His journey is no longer one of rescue, but of ritual, an endless orbit around the myths that gave his existence meaning.

Cooper Station itself offers no redemption. It orbits Saturn like a graveyard dressed as a city, filled with photographs of the dead and shadows of a planet that could not be saved but could still be mourned. Humanity endures, but it endures as memory made flesh, not as the triumphant frontier it once imagined.

Interstellar pretends for a moment that the answers might be scientific—that relativity, black holes, and fifth-dimensional beings might explain the ache. But the film’s true gravity is older, closer, more devastating. This is not a story about the exotic physics of survival so much as it is a spectacle of the ordinary experience of human time.

The folding of beginnings into endings, the haunting of every hope by memory, the impossibility of pure origins—these are not science fiction. They are the conditions of living. They are the way love stains the future before it even arrives. They are the way meaning comes pre-fractured, handed to us already broken. We don't long for an untouched future, as much as we might fool ourselves that we do. Instead, we long for what has already been lost and carry that longing forward.

In preserving the core function of mythological structure, Cooper becomes exactly what every myth demands: a sacrifice hidden in plain sight. A Dark Knight, if you will. The end bends back into the beginning. The myth survives only by becoming a ghost of itself.

Interstellar insists, almost defiantly, that its poetic soul is Dylan Thomas. "Do not go gentle into that good night," Cooper’s father-in-law recites, and for a moment, the film seems to believe it: that survival is an act of rage, that meaning comes from resistance. Yet, even Thomas, in his raging, knows that death is undefeated. Nostalgia endures not because it saves us, but because it's inevitable—the only grammar we've ever spoken.

The deeper cadence of Interstellar belongs, in fact, to T.S. Eliot: an ending that returns to its beginning, a struggle that finds not conquest but fragile reconciliation. As he wrote at the end of Little Gidding:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

It's the aching knowledge that survival is not a triumph over time, but an entanglement inside it. It's the understanding that endurance is not the defeat of death, but the faithful carrying of fracture forward, even when it can no longer be healed.

Cooper does not rage against the dying of the light. He bears it. He becomes its ghost. The fire he carries is not the blaze of revolt. It is the slow, cold fire of memory—a fire that burns inward, into the deepest structures of existence, into the folds where endings and beginnings are no longer separable, into the wound of time.

Interstellar closes with a gesture toward hope: "In the light of our new sun. In our new home." But the true gravity of the film is elsewhere. The sun might change. The home might change. But the structure of longing does not. The fracture survives every orbit, every voyage, every desperate act of survival. The future is not an escape from the past. It's the place where the ghosts we carry find new ground to haunt.

And among those ghosts, love lingers too—not whole, not victorious, but altered and enduring. It moves not as salvation, but as the slow-burning residue of memory, refusing to vanish even as it reshapes itself into myth. In Interstellar, as in life, the journey does not lead away from the wound. It leads deeper into it, until even the fracture becomes a kind of home—which it always was, anyway.