American

Ferris Bueller and the charm of the sovereign

He lies, he runs, he wins. But Ferris Bueller’s rebellion is no rebellion at all—it’s the system winking back.

"Bueller?... Bueller?"

It’s one of the most iconic scenes in American film: a monotone economics teacher stares out at a comatose classroom, rattling off the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act while the camera pans across glazed teenage faces. In the seat where Ferris Bueller is supposed to be, there’s only absence—a name called out to no reply. It’s meant to be a joke about high school boredom. But it also performs something deeper. Ferris is missing because he doesn’t need to be there.

While his classmates are stuck learning about economic collapse and protectionist policy, Ferris is off dancing in a parade, slipping past maître d’s, and monologuing to the camera with zero consequence. He doesn’t just skip school, he floats above it, buoyed by a system that not only tolerates his behaviour but quietly insists on it. The Great Depression may have been caused by bad policy, but Ferris Bueller is the kind of American the post-Depression system was built to reward: charming, white, frictionless, always winning.

The great lie of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is that it’s a story about rebellion. It’s not. It’s a story about sovereignty—the ability to operate outside the rules while still being protected by them. Ferris doesn’t face consequences, because he was never meant to. He performs resistance, but only to reaffirm his place at the centre of a world that exists to let him bend it. And the deeper twist? We’re in on it. The movie wants us to love him, and in doing so, we become the final pillar of his myth.

The illusion of risk

Ferris Bueller runs, but he is never running from real danger. The movie goes out of its way to suggest tension—there’s a ticking clock, a vindictive principal, a suspicious sister, and parents who might return home at any moment. Ferris hops fences. He dodges neighbours. He sprints across lawns to beat the garage door. On paper, it’s a chase. But in truth, it’s choreographed pageantry. Every risk is aesthetic. Every escape is a foregone conclusion.

This is not suspense so much as it is ritual.

Ferris isn’t fighting the system. He’s demonstrating its flexibility, showing how much it can be bent by someone who knows how to smile at the right time. He breaks the rules, yes. But only because the system was built to absorb that breakage, and in doing so, make itself seem magnanimous.

In Homo Sacer, Giorgio Agamben writes about the figure of the sovereign, someone who stands outside the law but still defines its limits. The sovereign is the exception that proves the rule, the one who can transgress without punishment because the system secretly depends on them. They don’t just escape justice—they authorize the escape itself.

Ferris is our sovereign. He skips school, fakes illness, steals a car, hijacks a parade, and narrates the movie like he’s producing it in real time. But he is never caught. Never punished. The adults who threaten his freedom are reduced to slapstick (poor Rooney), and the one person who sees through him—his sister—eventually joins his cause. Even Cameron, the closest the film comes to consequence, exists to absorb what Ferris never has to feel. He pays the emotional bill for the day off, while Ferris floats untouched.

The movie manufactures the appearance of risk while ensuring Ferris is never truly in danger. And this is the real trick: it isn’t about consequence, but about celebrating the kind of person who never has to worry about it.

Effortless American success

Ferris Bueller doesn’t change. He doesn’t grow. He doesn’t struggle or reckon or resolve. And that’s the point.

Where most protagonists face tension that transforms them, Ferris floats untouched through the day’s events. His charm is his shield, his smile the mechanism of propulsion. He simply moves from scene to scene collecting experiences as if life were a catalogue to browse. And yet, at the end of it all, he's rewarded not just with survival, but with admiration.

This is the dream that Ferris Bueller sells: not rebellion, but charm-fuelled reward. A version of American success where merit is measured not in effort but in likability, not in labour but in leisure. He doesn’t climb; he coasts. And still, everything works out.

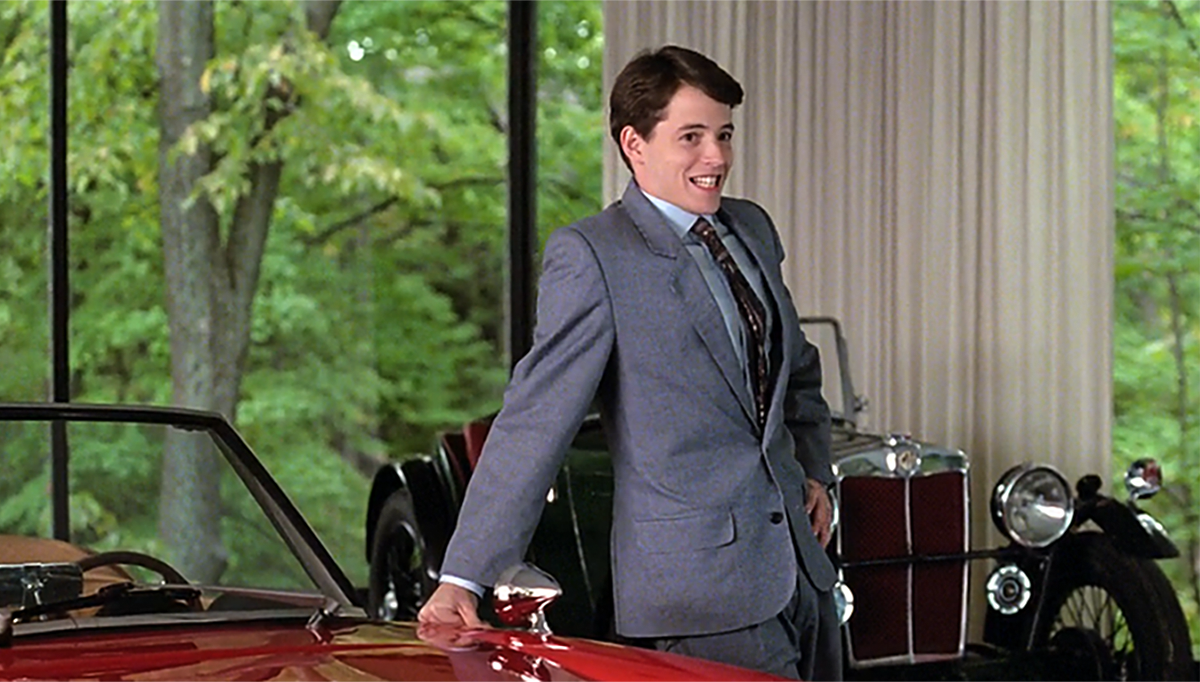

That’s what makes the film so seductive. Ferris isn’t mega rich, but he moves like someone who has inherited something more powerful than wealth—cultural immunity. He navigates elite spaces without being challenged, inserts himself into public spectacle without resistance, and drifts through institutions that are rigged to protect him. His day off becomes a high-speed tour of cultural capital: art, luxury, performance, spectacle. But there’s no real gatekeeping because the doors are already open.

The subtle brilliance of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is how convincingly it sells this movement as freedom. It’s not. It’s permission—granted invisibly by a system that hides its constraints behind the illusion of ease. Ferris doesn’t make the rules feel irrelevant; he makes them feel like they’ll bend for the right kind of person. That sentiment defines his advice to Cameron, but more strategically, his running metafictive commentary invites the viewer to believe that privileged person might be us.

It’s the same sleight of hand that animates our love of celebrity wisdom. Lines like "If you put your mind to it, you can do anything" ring out across commencement stages and social media feeds, not because they’re true, but because they preserve the myth that effort alone explains success. That’s capitalism’s favourite trick: to present exceptional outcomes as universally attainable, so long as you play the game.

Ferris doesn't showcase effort per se (quite the opposite), but he still plays the ideological decoy, proof that the system works—so long as you’re charming, confident, and savvy. And in contrast, Cameron breaks. He's the one who feels the weight of the day, who confronts his family, who stares into the abyss of the shattered Ferrari and says something has to change. His catharsis is real.

There’s a moment in the Art Institute that passes almost wordlessly, but it’s the emotional core of the film. While Ferris and Sloane flit through the galleries like tourists at play, Cameron stops. He stares into Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, a painting famous for its stillness, precision, and calm sense of order.

At first glance, it’s idyllic. Leisure made eternal. A perfect afternoon, just like the one the group is putatively having. But the longer Cameron looks, the less he sees a scene, and the more he sees fracture. The brushstrokes, the points of colour, the atomization of what once felt whole. The closer you get, the less real it becomes.

The film never speaks it aloud, letting it sit in an emotional register outside of exposition, but Cameron sees what Ferris never has to. The American dream isn’t seamless. It’s a million fragments straining to hold an illusion together. Up close and under examination, the system isn’t generous. It’s scattered, incoherent, uncaring.

Ferris skates on the surface because looking closely doesn't pay. To remain sovereign, he can’t afford to acknowledge the system as system. He must move through it as if its privileges are natural, inevitable, deserved. Cameron, by contrast, doesn’t have an epiphany so much as an encounter with the real. He sees the world not as a cohesive scene, but as lines and dots awkwardly assembled into a frame that only holds its shape from a distance.

And in that silent stare, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off finally admits its own secret: the day off is a fantasy, a pretty picture filled with fractures for anyone who dares to look closely enough.

The audience as enabler

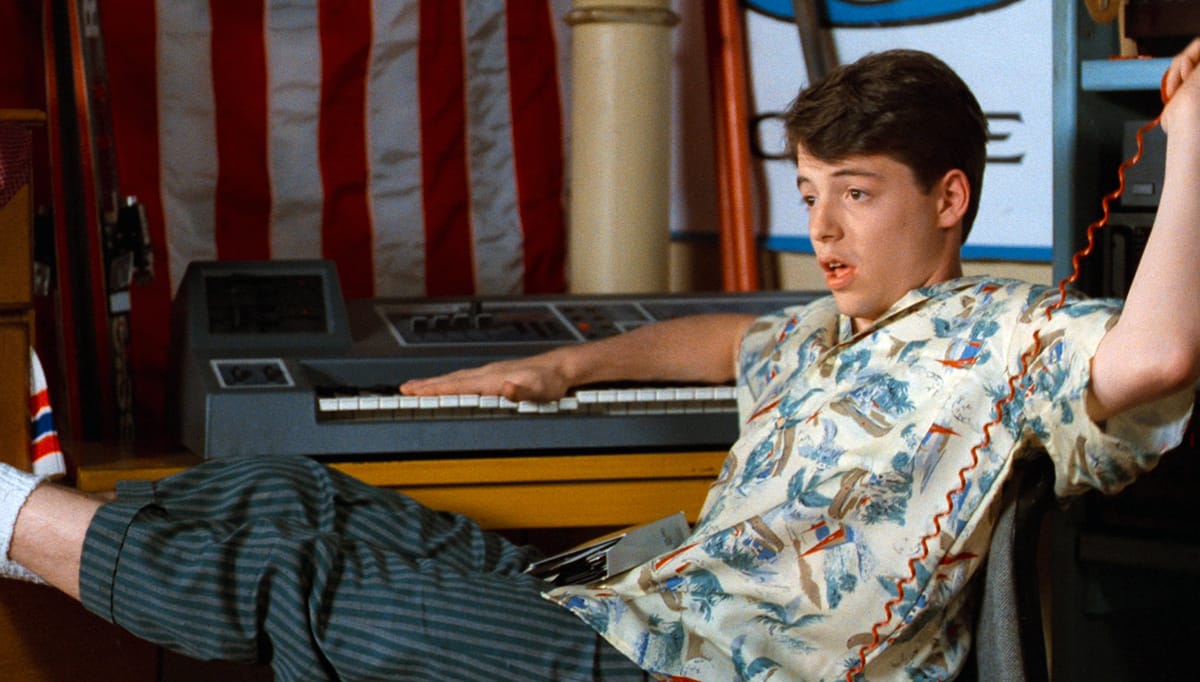

From the first moments of the film, Ferris speaks directly to us, charming the viewer as easily as he charms his parents. He tells us his tricks. He lets us in on the plan. He’s not just the main character, he’s the host, the narrator, the director of affect. He controls the frame, the rhythm, the mood. He defines the day, and we’re flattered to be along for the ride.

But this isn’t transparency. It’s actually a power move.

By bringing us in, Ferris defuses critique. He makes us complicit in his myth. We’re not watching him cheat the system in disgust. Far from it, we’re enjoying it, rooting for it, celebrating it. And when things seem like they might unravel, we know instinctively that they won’t. Because we’ve been trained to see Ferris as a natural winner, a benevolent manipulator, someone for whom the world bends.

That’s what makes his most quoted line so potent: "Life moves pretty fast. If you don't stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it." It sounds like wisdom. And maybe it is. But there’s a certain luxury that underwrites it. Only someone so untouched by consequence—so frictionless in his movements through the world—can hold this as his mantra. Ferris isn’t reflecting; he’s narrating. He’s curating an experience and branding it as revelation.

Compare this to Cameron. His best friend, we're told early on, "isn’t having any fun." He is consumed by inner reflection, but of a wholly different kind. Cameron’s day is not shaped by leisure but by dread—of his father, of his future, of himself. Where Ferris coasts through the world with unshakable certainty that things will work out, Cameron is immobilized by the opposite: the quiet suspicion that they won’t.

Even Jeanie, Ferris’s sister, seethes at his immunity. She follows the rules and still finds herself punished. Ferris breaks them and somehow floats. Her frustration isn’t just sibling rivalry; it’s the fury of someone who understands that the rules are real, and that they only bend for people like Ferris. She isn’t angry that the system is broken. She’s angry that it works exactly as intended: rigid for some, endlessly elastic for others.

As sovereign, Ferris’s so-called reflection isn’t really about presence at all. It’s about pleasure. The “stop and look around” he advocates is a tour through curated cultural capital: ball games, fine dining, luxury cars, art museums. It’s not about engaging with the world on its terms—it’s about mastering it, sampling it, styling it into a highlight reel.

Crucially, the line isn’t just offered to Cameron or spoken into the void. It’s delivered to us. It flatters the viewer with the illusion of shared insight, as if we too have earned the right to pause. But of course, we haven’t. We’re just watching someone who already has.

And then, having wrapped his perfect day and dropped his counterfeit wisdom, he dismisses us. "You’re still here? It’s over. Go home. Go." It’s not just a cheeky closing line—it’s an assertion of control. The sovereign doesn’t just escape consequence; he commands the narrative, ends the performance, and sends the audience away on his terms. We’re told the story is done, and we obey.

The smile that rules us

There’s a moment in the film—subtle but unforgettable—when Ferris stands at the top of the Sears Tower, forehead pressed to the glass, gazing out over Chicago. The city hums below. He’s not watching it so much as overseeing it. It’s tranquil, orderly, his. This isn’t the view of a teenager on the run. It’s the panopticon turned playground. A sovereign surveying the domain he’s already mastered.

Sloane stands beside him, poised, glamorous, and narratively passive. She smiles. She, too, floats. She plays queen for a day. But like so many figures in Ferris’s orbit, she has no arc of her own. She's there to reflect his charm, not complicate it. Even her quiet envy of Ferris’s certainty, her soft "you knew exactly what you were doing," is folded neatly into the performance of his perfection.

This is how the movie works. Not by hiding its mythmaking, but by styling it so well you want to believe in it. Ferris Bueller is the American fantasy in Ray-Bans: effortless mastery, no lessons, no loss. His day off isn’t a rebellion against the system—it’s the system congratulating itself. A ritual that reaffirms that charm beats labour, that consequence is negotiable, and that the right kind of person will always be forgiven.

It’s the first half of a Scorsese film.

The parade instead of the back entrance to the Copacabana. The Cubs game instead of the cocaine. The quiet Chicago suburb instead of the hollow glamour of Las Vegas or Wall Street.

Ferris lives in the part of Goodfellas and The Wolf of Wall Street before the paranoia, the indictments, the blood on the carpet. He floats through elite spaces with the ease of a steadicam—gliding, smiling, never tripping over the cords. But the difference is, in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the shot never cuts. The illusion never breaks.

This is the dream Ferris offers. It's not rebellion, but suspended youth. No consequences, no aging, no change. And the audience, like Sloane and Cameron, is asked to indulge the fantasy just long enough to believe in it.

And we do. We smile, we laugh, we wish we were him. Because Ferris isn’t just the sovereign of his world. He’s the sovereign we asked for and continue to mythologize.

No crash, no fall, no comeuppance. Just one perfect day, forever rerun, and a system that smiles every time we press play.